During the workshop I presented on a few topics, but mostly on accessibility of the Web in VR and performance. In the following few posts I'll be taking one of my lightning talks and expanding on it, line by line. I compared this with recording the lightning talks, taking my time, and hitting all of the points, but it seems better to get this into writing than to force everyone to put up with me 5-10 minutes at a time through a YouTube video!

My first performance talk was on the WebVR Content Pipeline. This is an area I'm supremely passionate about because it is wide open right now with so much potential for improvement. If we look at the commplicated, multi-tool build pipelines that exist in the games industry and use that as an indication of what is to come then that is a glimpse into where I'm thinking. If you want to see the original slides then you can find them here. Otherwise continue reading I'll cover everything there anyway.

The WebVR Content Pipeline Challenge

Not an official "fix this" challenge, but rather a challenging are to be fixed. I started this slide by reflecting on the foreign nature of build pipelines on the web. Web content has traditionally been a cobbled together mess of documents, scripts and graphics resources all copy deployed to a remote site. In just the past few years, maybe 5 at most, the concept of using transpilers, optimizers and resource packers has become almost commonplace for web developers. Whereas from 2000-2010 you might be rated on your CSS mastery and skillset, 2010 and onward we maybe started talking more about toolchains. This is good news, because it means some of the infrastructure is already present to enable our future build environments for WebVR.

My next reflection was on the complicate nature of VR content. You have a lot of interrelated components via linking or even programmatically through code dependencies. This comes across as meshes, textures, skins, shaders, animations and many other concepts. We also have a lot of experience in this area, coming from the games industry, so we know what kinds of tools are required. Unfortunately, even in games, the solutions to many of the content pipeline issues are highly specific to a given programming language, run-time or underlying graphics APIs. Hardware requirements make it even more custom.

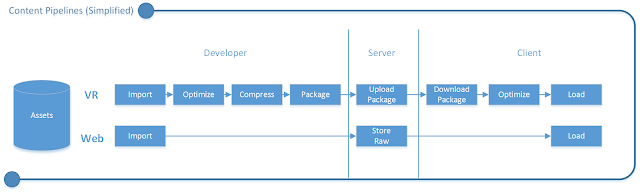

My final reflection was on the graphic below. This is a content pipeline example where you start with assets on the left and they get processed into various formats before they finally get loaded on the client. The top of the graph represents what a common VR or Game pipeline might look like with many rounds of optimization and packaging. On the bottom of the graph we see what an initial web solution would be (or rather what it would lack). The difference in overall efficiency and sophistication is pretty clear. The web will need some more tools, distribution mechanisms and packaging formats if it wants to transmit VR efficiently, while retaining all of the amazing properties of deploying to the web.

Developer - Build, Optimize, Package

The graphic shows three major stages in the pipeline. First we start with a developer who is trying to create an experience. What steps in the pipeline can he do before sending things onto the server? How much optimization or knowledge of the target device can be had at this level? Remember, deploying to the web is not the same as deploying to an application store where you know almost exactly what your target device will be capable of. While fragmentation in the phone market does mean some progressive enhancement might be necessary, the web effectively guarantees it.

My first reflection is that existing build technologies for the web are heavily focused on soling problems with large 2D websites. These tools care mostly about those resources which we currently see scaling faster than the rest. This mostly means script and images. Some of the leading tools in this space are webpack and browserify. Since some set of tools do exist, it means that plugins are a potential short term solution.

My second reflection on this slide was that the game industry solution of packaging was also likely to not be the right solution. This breaks to principles of th web that we like. The first is that there is no installation required. Experiences are transient as you navigate from site to site. Even though these sites are presenting to you a full application, they aren't asking you for permission to install and take up permanent space on your disk. Instead the browser cache manages them. If they want more capability, then they have to ask for it. This might come in the form of specialized device access or the ability to store more persistent data using Indexed DB or Service Workers. The second principle that packaging breaks is that of iterative development. We like our ability to change something and have it immediately available when we hit F5.

My third reflection is around leveraging existing tools. There are many tools for 3D content creation, optimization and transformation. Most of the tools need to be repacked with the web in mind. Maybe they need to support more web accessible formats or they need to come with the library that allows them to be used efficiently. In the future I'll be talking about SDF fonts and how to optimize those for the web. You may be surprised to find that traditional solutions for game engines aren't nearly as good for the web as they are for the traditional packing model.

Another option is for these tools to have proper export options for the web. Embedded meta-data that is invisible to your user but still consumes their bandwidth has been a recent focus of web influentials like Eric Lawrence. Adobe supported export for the web for years, but often people wouldn't use the option and would instead ship an image that was 99% meta-data. Many 3D creation tools have never had the web in mind, so they often emit this extra data as well or export in uncompressed or unoptimized formats, more similar to raw. Upgrading these tools to target WebP, JPEG and PNG as image output formats, or any of the common texture compression formats supported by WebGL would be a great start.

My final reflection for this slide was on glTF. I think that this format could be the much needed common ground format for sharing and transferring 3D content with all of their dependencies. Its well structured format means that many tools could use it as both an import and export target. Optimization tools will find it easy to consume and rewrite. Finally client side the format is JavaScript friendly so that you can transform, explore and render it however you want. I'll be keeping a close eye on this format and contributing to the Github repository from time to time. I encourage you to check it out.

Server - CDNs, CORS, Beyond URLs

Our second leap in our build pipeline is the server. While you can precompile everything possible and then deploy it, there will be cases where this simply isn't feasible. We should rely on the server to ingest and optimize content as well, perhaps based on usage and access. Its also a tiered approach for the developer who might be working on the least powerful machine in their architecture. Having the server offload the optimization work means that iteration can be done much more quickly.

For the server my first reflection is that we need smarter servers and CDNs that offload many types of optimization from the developers machine and their build environment off into the cloud where it belongs. As an example, most developers don't produce 15 different streaming formats for their video today and upload each individually. We instead rely on our video distribution servers to cut apart the video, optimize, compress, resample and otherwise deliver the right content to the right place without us having to think about the myriad of devices connecting to us. For VR the same example would be in the creation of power of 2 textures, precomputing high quality mipmaps or even doing more obscure optimizations based on the requesting device.

For device specific tuning we can look towards compression. Each device will have a set of texture compression extensions that it supports and not all devices support every possible compression type. Computing and delivering these via the server can allow for current and future device adaptation without the developer having to think about redeploying their entire project with new formats.

The second reflection is on open worlds. For this we need high quality, highly available content. There are a large number of content pieces that will be pretty common/uniform. While you could generate all possible cubes, spherical maps and other common shapes on the client, you can also just make them widely available in a common interchange format and available over CORS.

For those not familiar CORS stands for Cross Origin Resource Sharing and is a way to get access to content on other domains and be able to inspect it fully. An example would be an image hosted on a server, perhaps it contains your password on it, so it would not be served via CORS. While you could retrieve that image and display it in the browser you would not be able to read its pixels or use it with WebGL. On the other hand if you had another image which was a simple brick texture you might want to use it on any site in WebGL. For this you would return the resource with CORS headers from the server and this would allow anyone to request and use the texture without worry of information leakage.

I suspect a huge repository of millions or even billions of objects to be available in this way within the next few years. If you are working on such a thing, reach out to me and let's talk!

My last real reflection is that accessing content via URL is inefficient. It doesn't allow the distribution of the same resources from different locations with the caching we need to make the VR web work. We need efficient interchange of similar and reusable resources across large numbers of sites, but not put the burden on a single CDN to deliver those so that caching works as it exists today in browsers. There are some interesting standards proposed that could solve this or maybe we need a new one.

Not even a reflection, but rather a note that HTTP/2 pushing content down the pipe as browsers request specific resources will be key. Enlightening the stack to glTF for instance to allow for server push of any external textures will be a huge win. But this comes with a lot of need for hinting. Am I getting the glTF to know the cost of an object or to render it? I will try to dedicate another future post to just HTTP/2, content analysis from the server and things we might build to make a future VR serving stack world and position aware. I don't think these concepts are new and are probably in heavy use in some modern MMORPG games. If you happen to be an expert at some company and want to have a conversation with me on the subject I would love to pick your brain!

Client - Progressive Enhancement

The last stage in our pipeline is on the client. This is where progressive enhancement starts to be our bread and butter technique. Our target environment is underpowered and at the high end of that spectrum will be LTE enabled mobile phones. Think Gear VR, DayDream and even Cardboard. Listening to Clay Bavor talk about the future it is clear Google is still behind Cardboard and admits to there being millions of units out there already with many more millions to come. Many people have their first and only experiences in VR on Cardboard.

Installation of content is no longer a crutch we can rely on. The VR Web is a no install, no long download, no wait environment. Nate Mitchell at OC3 alluded to this in his talk when he announced that Oculus would be focusing on some key projects to help move the VR Web forward. I still consider Oculus a team that delivers the pinnacle of VR so to take on the challenge of adapting the best VR experiences possible to this rather harsh set of mobile and web requirements is pretty epic. That is what the rest of this slide covers.

My first reflection after noting the requirements is that of progressive texture loading and fallback all the way to vertex colors when textures aren't available yet. The goal of VR is to get people into an immersive environment as fast as possible. Having a long loading screen breaks this immersion. The power of the web is the ability to go from site to site, without breaking your immersion, the way you do today when navigating between applications (or when you have to download a new application to serve a purpose for which you just gained a need). We also aspire to have VR to VR jumps work like they do in the sci-fi literature or in movies. A beautifully transparent experience as you switch from world to world.

We can achieve this with good design and since the VR Web is just starting we have the opportunity to design it right. My only contribution for now is to load your geometry with simple vertex colors, follow up with lightweight textures and finally, once the full texture is loaded and ready, upgrade to the highest quality experience. But don't block the user or lower your framerate significantly to jump up to that highest quality if it is going to be disruptive to your user. This will require some great libraries and quite a bit of experimentation to find all of the best practices. Expect more from me on these subjects in future articles as well.

My second reflection is on the importance of Service Workers. A feature designed to make the web offline can also be a powerful catalyst in helping the VR Web instantly load and become fully progressive. The features I think that are key in the near term are the ability to implement some of the prediction and prefetching for things like glTF resources. As the Service Worker intercedes it can fire off the requisite requests for all of the related textures and can cache them for later. We can also build in the progressive texture loading into the service worker and have it optimize for many different variables to deliver the best experience. Its basically like having the server of the future that we all want, but on the client and under our control.

Another feature of the Service Worker is understanding the entire world available to the experience and optimizing based on the current location and orientation information. This information could also fit into the future VR server, but we can test and validate the concepts in the Service Worker long before then.

My last reflection on the client is that there are some well defined app types for which we could deliver the best possible experiences using common code available to everyone, perhaps augmented by capabilities in the browser. This is highly controversial since everyone points out that there is indeed a base experience but that it is insufficient and customization is a must. I disagree, at least for now. Its like arguing against default transport controls in the HTML 5 video player. Why? 99% of your web developers will use them to provide 20% of the scenarios in the long tail of the web. Sure there is a 1% that develops top sites and accounts for 80% of the experiences and they'll surely want to add their own customization, but they are also in the best position to create the world class optimization and delivery services needed to make that happen.

To this end, I think its important that we build some best of class models for 360 photos and videos and optimize this into the browser core while VR is still standing up. These may only last for a couple of years, but these are the formative boot strapping years where we need these experiences to amaze and entice people to buy into the VR Web that doesn't quite exist yet.

Bonus Slides

I won't go into details on these. They are more conversation starters and major areas where I have some internal documentation started on what we might propose from the Oculus point of view. I'll rather list them here with a sentence describing some basic thoughts.

- Web Application Manifests - If these are useful for describing web pages as applications they can be used to describe additional 3D meta-data as well.

- Texture/Image Optimization - Decoding image types, compressing textures on the device, etc... Maybe the realm of Web Assembly, but who knows.

- glTF - Server enlightened data type with HTTP/2 server push, order optimized, LOD optimized and full predicted based on position and orientation.

- Position Aware Cube Maps - Load only visible faces, with proper LOD, perhaps even data-uri encode for the initial scene load.

- Meta Tags/HTTP Headers for Content Hinting - Initially this was only position and orientation so that the server could optimize but has since grown.

What's Next?

If you find things here interesting you can contact me now at justrog@oculus.com and we can talk about what opportunities might exist. I'll also be reaching out to you as I find and discover experts. I like to constantly grow my understanding of the state of the art and challenges that exist. Its my primary reason for joining Oculus, so that I could focus on VR problems all day, every day!

I have 3 more talks that I delivered at the conference, each prepared similar to this one as a blog post. I'll finish the perf series first and the I'll end with my rather odd talk on Browser UX in VR. Why was it odd? Stick around and I'll tell you all about it in the beginning of that post.